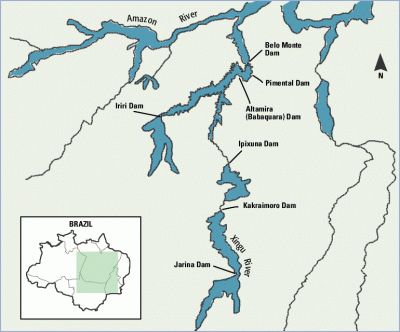

At Belo Monte (or “Beautiful Mountain” in English), the then US$ 10.6 billion dam proposed by Altamira would inundate 7.6 million hectares of rainforest, submerging the lands of eleven different Brazilian indigenous groups, one of which was the Kayapo.

What was different about this indigenous group was their innovative approach to halting the immense project. The Kayapo, while living by traditional means and in isolated villages, were anything but unaware of their global context. The Kayapo realized the world saw indigenous people as having a connection to the land that was otherwise lost. They used this conception to promote their indigeneity and ownership of the land. Kent Redford later termed this phenomenon as one of the “ecologically noble savages.” It was for this reason that any public image of the Kayapo was in full ceremonial garb.

In fact, they knew exactly how the world saw them, and exactly how to play-up identity politics to their advantage. When Payakan and Kube-i, Kayapo chiefs, toured the West to lobby against the dam, they did everything to preserve this identity. They delivered symposia on the Native preservation of biodiversity and ecological knowledge of Amazonian flora and fauna, and partnered with the David Suzuki Foundation and the World Wildlife Fund.

They also employed the then novel idea of enlisting celebrities to champion the cause. The precursors to modern celebrity philanthropy can be traced back to Sting, posing for photos with Payakan and other Kayapo. At the time, celebrity presence was a groundbreaking strategy in gaining sympathy and attracting media.

It worked. Public outcry and immense protests forced the Brazilian government to back off the project. Through a combination of international attention, persistence and ferocity of the Kayapo themselves and cooperation with environmental groups, the Belo Monte dam was not built. That, however, was in the 1980s.

Now, Brazil’s growing population and rapidly expanding economy are changing the stakes. The slew of celebrities and an incredible movement to the international recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights and land claims can no longer stop the flood from coming. In January 2011, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) issued a permit that allowed the construction of the dam to begin. The now US$ 17 billion project was immediately overcome by protests and lawsuits, and was forced to halt in February. Olindo Menses, a judge, turned the decision over, and although the project was jostled back and forth in the legal system the ultimate decision was not in Kayapo favour.

If constructed, the Belo Monte dam would be the third largest in the world. While the dam could provide electricity to a projected twenty-three million people, it would flood out five hundred square kilometers and fifty thousand people. Further, the project is hugely inefficient, producing a mere ten percent of its maximum capacity during the dry season and otherwise guaranteeing only thirty-nine percent of its maximum capacity. In contrast, one hundred kilometers of the Volta Grande (or “Big Bend” in English) will be subject to permanent drought. The dam will affect fish stocks that local peoples rely on for subsistence. Greenpeace dumped three tones of manure outside the Brazilian Agency for Electrical Energy in Brazil to demonstrate the “Beautiful mountain of sh*t” that Belo Monte would become.

Old tactics have once again forged their way into this conflict. Filmmaker James Cameron put together an aptly titled film “Message from Pandora” in 2010 as an effort to support the indigenous peoples. Contempt for the project is once again surfacing from International environmental organizations such as Amazon Watch. Indigenous groups have mobilized and protested. Yet, the resurgence of efforts previously seen have fallen short of derailing Belo Monte.

Proponents of the Belo Monte dam say that the project has been researched, considered and reworked unlike any other preceding it. For the better part of thirty-five years, they have argued that 18,700 people will be employed. Additionally, countless citizens look to the 11,200 megawatt capacity of the dam with hopes for a better future. Norte Energia promises development for the indigenous peoples affected, and predicts that the energy produced would contribute to Brazil’s urban development.

However, of those several thousand initial jobs only two thousand are permanent. The rest of the migrant workers will cut more forest to live, and deplete already low natural food supplies. The destruction of indigenous territory is prohibited by the Brazilian constitution. Many worry about the immense impact the dam will have on the Amazon jungle, its rivers and the living beings that depend on them. In a country where eighty percent of total energy comes from hydroelectricity, a great game of balancing developments must now be played.

Photo: International Rivers (flickr)

Log in

Log in