The Ukrainian conflict, like most political phenomena, is multi-dimensional and highly complex. As such, it calls for a holistic – dialectical, if you wish – approach. But to judge by American and NATO spokespersons and by their mass media, there is only one really decisive factor that explains everything: Russia’s imperialism, Vladimir Putin’s determination to dominate and further dismember the Ukraine as part of his plan to restore the Soviet empire. In this simplistic view, Ukraine, with benevolent support from the West, would be quite capable of dealing with its problems and would soon be on its way to becoming a prosperous, Western-style democracy.

My view is quite the opposite: the roots of the Ukrainian conflict are domestic and profound; outside intervention, while significant, is a secondary factor. Given limitations of space, I will, therefore, focus on the internal situation. But I will necessarily, if more briefly, also address the international dimensions of the conflict. This is also the more necessary since the Canadian government has been particularly zealous in its support for the Ukrainian government and in condemning Russia as solely responsible.

My goal is to offer a framework that can help in understanding and evaluating the mass of information about the conflict coming from governments and the media.

A Deeply Divided Society

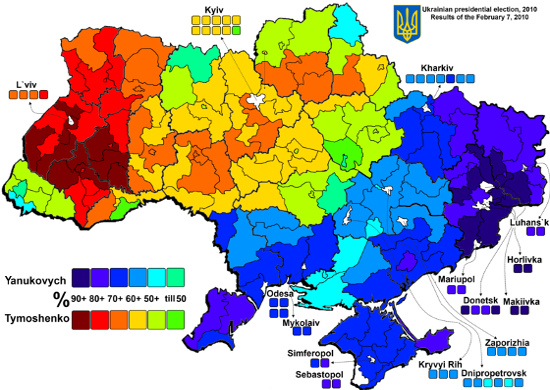

Ukraine is a deeply divided society – along lines of language, culture, historical identity, ethnicity, religious affiliation, attitudes to Russia, as well as real and perceived economic interests. Since Ukraine became independent in 1991, these divisions have been manipulated and fostered by corrupt economic and political élites with the aim of distracting popular attention for their criminal activities and to gain advantage in intra-élite competition. This manipulation, on the background of widespread poverty and economic insecurity, has prevented popular forces from mobilizing to oppose this oppressive ruling class, the so-called ‘oligarchs’, who have run the economy into the ground while fantastically enriching themselves. Since independence, Ukraine has lost over 13 per cent of its population, down to 45 million. Of those, several million are working abroad as cheap labour in Russia and the EU.

About half of Ukraine’s population speaks Ukrainian in everyday life; the other half – Russian; and practically everyone can speak both languages well enough. The three western, overwhelmingly ukrainophone, regions joined the rest of Ukraine in the 1940s after two centuries under oppressive Austro-Hungarian, then Polish, rule. The southern and eastern parts first became part of Ukraine at the end of the Russian civil war in 1920. Until 1991, Ukraine had never existed as a state, except for a very brief period during the civil war.

The population of the western regions is deeply nationalistic; and at the centre of that nationalism at present is a profound fear, mixed with hatred, of Russia and, to varying degrees, of Russians. The eastern and southern regions, mostly russophone, have strong cultural and ethnic affinities, as well as political sympathies and economic ties, with Russia. The situation in the centre is mixed. Historical memory plays a big role in the divisions: the heroes of the west collaborated with the German occupation in World War II and participated in its crimes; the heroes of the east and south fought against fascism and for the Soviet Union. In fact, there is hardly any major historical event or figure going back centuries upon which the two poles agree. There are also economic interests: the east is more industrial and closely integrated with the Russian economy, by far Ukraine’s leading trading partner; the western is dominated by small towns and is more agrarian.

These differences express themselves in opposing political positions, in which irrational fears play a not insignificant role. The population of the west, with some support in the centre, has generally been more active politically and has sought to impose its culture, which it considers the only truly Ukrainian, on the rest of the country. People from the western regions constituted a disproportionate part of the Maidan protesters. Opinion surveys consistently show the Ukrainian population to be split on major issues, although most, both east and west, have perceived the successive governments as corrupt and dominated by oligarchs. The major issue of contention has been the legitimacy of the central government. The one formed after Victor Yanukovych’s overthrow has strong support in the west and, to a significant degree, also in the centre, which has seen a nationalistic upsurge; the population in the east and south widely despises and fears the government, which it considers illegitimate.

What was Maidan?

The initial issue in the Maidan protest was the fate of an economic agreement that the then President Yanukovych had been negotiating with the European Union. Yanukovych, who was identified with the russophone east and south, decided (wisely in my view) to suspend the negotiations and accept Russia’s offer of a $15-billion loan. But when he resorted to repression against the protesters, the protest was transformed into a protest movement against the government itself, its repressive, corrupt nature. Armed neo-fascist elements from the West increasingly became involved, further radicalizing the protest, attacking police, occupying government buildings, and finally convincing Yanukovych to flee on February 21.

A provisional government was then formed by not altogether constitutional means. It consisted exclusively of politicians identified with the western, nationalist regions and included several neo-fascists. Politicians identified with the west, including some oligarchs, were put in charge of eastern regions, whose population widely viewed the new government as hostile.

Donbass Insurgency

Copying the Maidan protest and earlier actions in the western regions that had been directed against Yanukovych’s government, groups of local Donbass citizens already in February began to occupy government buildings, calling for a referendum on the region’s autonomy and possibly its secession and annexation to Russia. These groups were initially unarmed, nor were they for the most part separatist. As their compatriots in the west had done earlier against Yanukovych, they were demanding local autonomy as a measure of protection against a hostile central government.

Kiev’s reaction only confirmed the worst fears and prejudices of the Donbass population. Under the impression of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and spurred on by its own fervent nationalism, the new government in Kiev made no serious effort to reach out to the population of the east. Instead, almost immediately it declared the protesters “terrorists” and launched a so-called “anti-terrorist operation” against them. There was no genuine desire to negotiate, but to crush militarily. And since the Ukrainian army was a mess and had little taste for fighting its own people, the government created and armed a National Guard, consisting of poorly trained volunteers that included ultra-nationalists and neo-fascists. As if that were not enough to confirm the fears of the easterners, some 45 anti-government protesters were massacred in Odessa on May 2, a crime for which Kiev blamed the protesters themselves, as well as unidentified Russian provocateurs.

None of this changed fundamentally after the presidential elections of early May. President Petro Poroshenko has also made no serious effort to negotiate an end to the conflict. The indiscriminate shelling of civilian centres in Donbass by the government only confirmed its illegitimate, alien nature in the eyes of the local population.

There is not much that is known for sure – at least by myself – about the relations between the local population and the armed insurgents in the Donbass. Moreover, these relations undoubtedly evolved over time. But it is clear that the insurgents were, and still are, in their majority local people and that, at least until relatively recently, they enjoyed varying degrees of sympathy among the population, most of whom, however, did not want to separate but only a measure of self-rule. I imagine that today the local population mostly wishes only for an end to the fighting and a measure of physical security.

The insurgency itself underwent radicalization over time, especially with the influx from Russia of Russian nationalists. In any case, although the government in Kiev has made an offer of amnesty to those who have not committed serious crimes, the militias no doubt fear only the worst if they were to surrender.

The Central Government

Ukraine’s political regime differs from Russia’s in that in Ukraine the oligarchs dominate the state and the mass media. In Russia the regime is ‘Bonapartist’, that is, the political élite dominates the oligarchs, even while serving their interests. That is essentially why there has been more political pluralism in the Ukraine. Whether that has been more beneficial to Ukraine’s working-class is another question. As for the economic and social situations, Ukraine is basically Russia but without oil and gas.

A glance at the political career of president Poroshenko, billionaire owner of a confectionary empire and auto plants, offers some idea of the nature of the regime. Poroshenko was a founding member of the Party of Regions in 2000, the political machine that eventually brought Yanukovych to power in 2010. But a year later, Poroshenko left the party to become a leading financial backer of Our Ukraine, a party closely identified with the western regions and with Ukrainian nationalism. He backed the so-called Orange Revolution at the end of 2004 that brought to power Viktor Yushchenko, a staunch pro-West Ukrainian nationalist. Poroshenko became his Foreign Minister, advocating NATO membership (a position rejected by a strong majority of the population). But he lost his job in 2010 when Yanukovych won the presidential elections. Poroshenko nevertheless returned in 2012 to serve Yanukovych as Minister of Trade and Development. But he left that post after eight months to return to parliament as an independent. In short, this is the career of an inveterate political opportunist, who, like the rest of his class, subscribes to the Russian adage: “Where my fortune lies, there lies my heart.”

Poroshenko, to the extent he has principles, does not belong to the more extreme wing of Ukrainian nationalism, although he has called the Donbass insurgents “gangs of animals.” (Prime Minister Yatsenyuk, beloved by Western governments, has called them “subhumans.”) But in any case, Poroshenko shares power with a cabinet and parliament that include extreme right-wing elements. And because of the army’s weakness, he has had to rely heavily on ultra-nationalist paramilitary forces to prosecute the war. For example, the cease-fire, to which he agreed to on June 21 and apparently wanted to prolong while pursuing negotiations, was cut short after a demonstration by so-called “volunteeer” battalions, recruited largely from ultra-nationalist far-right elements. Then there are people like the multi-billionaire governor of Dnepropetrovsk region, Igor Kolomoiskii, who payrolls his own army, the Dnipro Battalion; or the increasingly popular parliamentary deputy, the right-wing populist thug, Oleg Lyashko, who has personally commanded volunteer battalions in the Donbass. Poroshenko also has to consider the upsurge of nationalist sentiment in the wake of Crimea’s annexation and the massive propaganda campaign against Russia in the oligarch-controlled media that has gone well beyond the typically nationalist elements of Ukrainian society. Finally, the war and national emergency are needed to distract popular attention from very harsh austerity measures that are really only in their first stages.

International Dimension

Although the conflict is fundamentally a civil war, external forces have played a significant role. The “West” (U.S., EU, NATO) bears a heavy responsibility for its unflinching support and encouragement of the Ukrainian government in its pursuit of an exclusively pro-Western political and economic orientation. In view of Ukraine’s deep internal divisions, that policy is fatal to the integrity of the state and the peaceful development of the society. Moreover, from the moment the internal divisions assumed the form of an armed confrontation, the West has unflinchingly supported both the actions and the propaganda of the Kiev government. That propaganda portrays the Russian government as solely responsible for the conflict and is silent about Kiev’s own intransigence, its serious war crimes against the non-combatant population of Donbass and the serious economic suffering it is imposing on the entire population.

An analysis of Western interests and motives is beyond the scope of this presentation. But it is quite obvious that since the fall of the USSR, the U.S., with more or less active support from Europe, has followed a course aimed at maximally limiting Russia’s geopolitical influence and at surrounding it with unfriendly states. Despite solemn promises made to Mikhail Gorbachev, these states have been integrated into NATO, from which Russia is excluded. Where integration into NATO has not been possible or desirable, regime change has been pursued. That has been the West’s policy in Ukraine. The EU’s association proposal, which was at the origins of this crisis and which contained clauses pertaining to defence policy, forced this deeply divided country to choose between Europe and Russia. (A national poll from December 2013 found that 48 per cent agreed with Yanukovych’s decision not to sign and 35 per cent disagreed. In western Ukraine, however, a full 82 per cent disagreed.)

The Russian government saw the very open and active support for the Maidan protests and then for the provisional government and its policies as being in direct line with that policy of “containment.” The annexation of Crimea, that does not appear to have been long in the planning, was, at least in part, a message to the West: only so far!

Ukrainian and Western claims notwithstanding, Putin does not aim to further dismember Ukraine, nor does he plan to recreate the Soviet empire. While it may not be his preference, he is prepared to accept Ukraine’s neutrality and its closer economic ties with Europe. What he does not want is a hostile, exclusively Western-oriented Ukraine. European Russia, which has the bulk of its population and industry, shares a 2500 kilometer border with Ukraine. Given the history of the twentieth century, Russia’s sensitivity to this question should not be too hard to understand, even apart from the deep historical, cultural, ethnic, family and economic ties that bind the two societies.

But Russia is not without its own responsibility in this conflict. I take issue with some on the left (including the Russian left), who support the annexation of Crimea and Russia’s involvement in the civil war as justified anti-imperialist policies. Meanwhile, others on the left have taken the opposite position, essentially embracing Kiev’s version of the conflict.

It goes without saying that Western condemnation of the annexation of Crimea is profoundly hypocritical in view of the West’s longstanding and continuing history of imperialist aggression and disregard for international norms. One thinks of the detachment of Kosovo from Serbia and the invasion of Iraq, as only two recent examples of this. There is, moreover, no doubt that the vast majority of the population of Crimea, which never felt itself to be Ukrainian, was happy, many even overjoyed, with the annexation. Local Crimean governments have wanted as far back as 1992, only to be rebuffed by Russia. In every national election, Crimeans have voted overwhelmingly for pro-Russian Ukrainian parties.

As a citizen of Canada, a NATO member with a right-wing government that has been a zealous cheerleader for Kiev, I admit that my first instinct was to support Putin as acting in defense of his country’s national interests against Western aggression. But that is a mistaken position.

If the annexation of Crimea was not part of a master plan to restore the Soviet empire, neither was it motivated primarily by legitimate concern for Russia’s national interests. Indeed, one has to wonder what might constitute a national interest in a class-divided society where vast wealth is concentrated in the hands of so few and which is dominated by a corrupt, authoritarian government.

In any case, Putin himself has not explained the annexation in terms of geopolitical interest. In his speech in March dedicated to Crimea and in another in early July at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he referred instead to the duty to protect Russian populations outside Russia’s borders. This is an appeal to ethnic nationalism. And it (as with the wars against Chechnya and Georgia before) has been extremely successful in boosting Putin’s popularity, at the same time as it narrowed the already limited space for opposition to his regime.

But even from the point of view of geopolitical interest, the annexation of Crimea appears incredibly short-sighted and harmful to Russia. The annexation, along with Putin’s justification, gave a major boost to anti-Russia nationalist paranoia in Ukraine. At the same time, it encouraged the armed resistance in Donbass to Kiev. So while Russia, sincerely I believe, has consistently called for a cease-fire and a negotiated settlement, the annexation, in fact, has fed the armed conflict. And Russia is also directly contributing to the conflict, since the groundswell of nationalist sentiment in Russia forces Putin to allow an unofficial, limited flow of combatants and arms to the Donbass, even while Putin has no intention of intervening in force to rescue the militia. (I could be proved wrong but I strongly doubt it.)

And so instead of protecting the Russian population of Donbass, Putin has in fact contributed to the deterioration of its situation and has undermined Russia’s ability to effectively defend its interests.

But the annexation has also been very injurious to Russia’s own situation in the world. By giving a major boost to anti-Russian nationalism and the government in Kiev, Putin ensured that Ukraine will henceforth be firmly within the Western camp and hostile to Russia. He has also helped to solidify NATO as a hostile alliance aimed at containing a supposedly expansionist Russia. And he has deprived Russia of what had been its fundamental argument against U.S. and NATO aggression: respect for the international norms of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states and for their territorial integrity.

Some make the argument that Putin had to secure Russia’s naval base in Sevastopol. But the threat was only potential – although over the years high Ukrainian officials have spoken of handing it over to NATO – and its securing hardly outweighs the geopolitical damage to Russia incurred from the annexation. (Putin seems to have miscalculated Europe’s, especially Germany’s, willingness to follow the U.S. in a crusade against Russia.) Moreover, if Sevastopol were really threatened, the base could have been moved to Russia’s Black Sea port in Novorosiisk. The cost of the move would probably not be much greater than the losses that will be incurred from the Western sanctions.

Conclusion

The solution, in principle, has always been evident: a cease-fire monitored by international observers, followed by negotiations, on the sole condition of acceptance of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. The subject of negotiations would be the delegation of power to regional and local elected governments. This is the famous “federalization,” supported by Russia and most of the population of Donbass but rejected by Kiev and the West, who claim it is merely a cover for separation of Ukraine’s east and its annexation by Russia.

But in so deeply divided a society, federalism can, in fact, be an effective measure against separatism. (If Canada were not a federal state, Quebec would have separated years ago.) But things might have probably already gone too far. Kiev, backed by the West, will not hear of a cease-fire. It wants a full surrender or decisive military victory. And, although unlikely, domestic pressures might finally convince Putin to intervene directly. In any case, the future does not appear bright for a unified Ukrainian state. •

David Mandel teaches political science at the Université du Québec à Montréal and has been involved in labour education in the Ukraine for many years.

Log in

Log in