Lack of arable land and fresh water, which result in agricultural change, are exacerbated by climate change and population growth. This is likely to have a snowball effect on food security worldwide. The recent price hikes resulted in widespread riots. The global panic was worsened by restrictions put in place by grain exporting countries such as Russia, Argentina and Vietnam to limit agricultural exports in an attempt to keep domestic prices low. The urge by rich nations to secure arable land abroad is on the rise to safeguard domestic food supplies. Where does this leave rights to land and fresh water in developing areas? Unfortunately, the relationship between foreign investors and developing country citizens is not one of equal opportunity.

According to the World Bank, more than thirty-five million acres of land were bought or leased in Africa, Asia and Latin America, where approximately eighty percent of vacant farmland is located. This land acquisition has sparked controversy as its sole purpose is to serve needs of investors, many of whom come from oil and gas-rich states, such as Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, where water and food security are at “extreme risk.”

The route to this controversy is twofold. Firstly, the cost of leases or purchases is shockingly low, which appeals to investors seeking high rates of return. Secondly, most of the countries where land is bought rely heavily on food aid. Overall, thirty-five African countries are net importers of food. Agricultural investment could lead to important development towards ensuring food security in these countries. However, the focus of investment on export-led agriculture has made them vulnerable to price shocks on the international market and to currency exchange volatility, as reported by Olivier de Schutter, the UN special reporter for the right to food. As well, the risk of widespread hunger is heightened in regions where food resources are exported rather than consumed domestically.

Emerging economies, such as China, India and South Korea also aim to secure the resources necessary to fuel their rapid growth. To do so, they have looked into investing in countries with the most potential for irrigation to grow grain. Today, more grain is produced worldwide, but surpluses are much smaller. Such is the case in the US, where fertile land is diminishing and the nation is unable to keep up with its demand for grain.

Many of the land investment deals are sealed in countries that are in post-conflict reconstruction. Plagued by weak governance, corruption and a lack of transparency, there is limited screening of the proposals. Environmental Impact Assessments are rarely carried out, without which commercial farming and exploitation of land can lead to absolute water shortages. Investing countries are essentially exporting their water shortages abroad, as water rights are in most cases poorly, if at all administered.

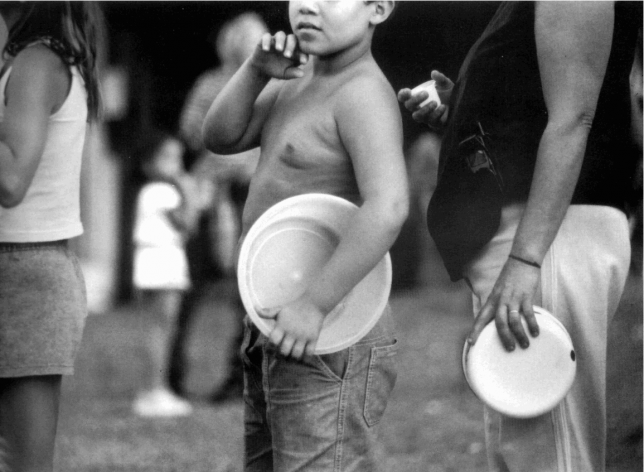

Agriculture and the ability to grow crops increasingly gives geopolitical leverage. However, when the notion of land is intrinsically linked to the question of identity, livelihood and food security, can land be something you just buy?

A case study of Ethiopia, the Bechera Agricultural Development Project, presents the simultaneous dangers and opportunities of the “Land Rush” in Africa. The Indian company Karuturi Global Limited acquired 10,700 hectares of land from Oromiya Regional state for a period of thirty years to cultivate maize and palm trees without conducting a preliminary environmental survey. The report published by the International Land Coalition showed a lack of communication between the foreign investors and the local population, who failed to see the development they were first promised in the form of improved infrastructure and social services. Instead, the local community was displaced and unable to access water and grazing points for cattle. Furthermore, the process of land acquisition was not conducted transparently. As a result, the eighty-five percent of Ethiopians whose livelihood depends on agriculture no longer have sufficient surplus to export.

The negative consequences of commercial farming projects are numerous and include loss of grazing land and loss of wetlands as a reserve for biodiversity. The issue of water is also a main concern, as the hydrological conditions are affected in several ways. With mechanized commercial farming projects comes the use of fertilizers and pesticides in large quantities, causing chemical run-off that worsens the quality of water.

There are many recommendations that can be made towards ensuring that the land deals do not imperil people’s livelihoods and food security. On the one hand, investors must promote local participation in economic activities and proceed in a transparent manner. Moreover, it is the responsibility of governments to clarify the nature of the deals and investment they want to draw. The population should be consulted and be aware of the costs and benefits of any future activities taking place on their land and how they will be shared. Social and environmental assessments are necessary before closing any deals, especially long term deals (lasting fifty to one hundred years) where the sustainable use of natural resources is crucial. In the same manner, purely speculative acquisitions should desist. Finally, greater efforts are needed in many countries to secure local land rights and prevent people from being dispossessed of their land.

Overall, the principle of free, prior and informed consent and robust compensation regimes should be a cornerstone of government policy and must be integrated in national legislation. Hopefully this will allow for the rights of developing countries to land and water to be respected in the international arena.

Berlin, Germany

Log in

Log in