Karamat Ali is a Founding Member and Executive Director of the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education (PILER), a Founding Member of the Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy, and the Pakistan Peace Coalition. He is a renowned labour and development activist in Pakistan, and has spoken and written extensively about peace movements, labour organization, development, and politics in South Asia.

What conclusions have you reached from your work with PILER, your experience as a labour activist, and your understanding of the South Asian region?

I come from a trade union background; I worked in a factory myself and eventually became a full time trade union organizer. In Pakistan, there have been periods of great mobilization, of youth, student, and labour organization, predominantly in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I got involved during those times. We mobilized against the dictatorship, for labour rights, for student’s rights, and for democratization. However, this movement was crushed in the late 1970s; Pakistan experienced another military dictatorship, which imposed Marshall Law. Under Marshall Law, fundamental rights don’t exist, and military regimes are particularly harsh on labour organization. We went from a time when activists, influenced vaguely by socialist ideas, were willing to take massive collective action, when factories were occupied and run by the workers themselves for months, and when workers fought against the police and in some cases against the armies. Then there was a backlash. While we looked back to determine what went wrong, we realized that, amongst various other things, what was lacking was workers education and training. During periods of great mobilization, people just need to come out, to show up. But, how do people deal with their issues during the period of non-mobilization? We didn’t know anything about that; we thought that collective action could solve everything.

That’s how we started PILER. We tried to understand the issue of militarization; why it happens, how to deal with it, how to mobilize against it. We wanted to understand this flux of military regimes and civilian governments. We wanted to learn about democratization. From these interests, a variety or interrelated issues crop up: conflicts with neighbours, the issue of peace. We took up these issues, and many more. However, the issue of regional cooperation becomes, arguably, the most important.

In your lectures and writings, you emphasize the importance of regional solidarity in South Asia. How do processes of democratization and demilitarization relate to the need for regionalization and peace in South Asia?

If you look at the globe, the whole world is now more or less organized regionally, on the basis of regional cooperation, and of course these regions are all focused on economic integration. The neighboring countries in such regions are grouped together historically and culturally. Regions normally involve a common language, history, and/or culture, and in some cases, a long history of conflict.

Take the example of the European region. All the big wars have originated in Europe, regardless of where they were fought. There exists a history of conflict and rivalry amongst the three major European nations: the British, the French, and the Germans. The European nations fought over territories elsewhere; they were all colonizers. After much destruction and millions of deaths, the European colonizers concluded that it was time they started cooperating. They had destroyed each other’s economies to such an extreme that they could no longer survive in a situation of perpetual conflict. Furthermore, there was another emerging economic and political power, which had the means to impose certain imperatives upon the warring nations: communism. Communism was a power to reckon with, its very existence threatened the economic order that all these countries had in common: capitalism. Many factors combined which led to a reconstruction of regional solidarity in Europe and also, simultaneously, the process of decolonization. The whole world was changing. In the European scenario, we witness the gradual emergence of a capitalist region in Europe, after periods of intense conflict on a global scale.

This led to the gradual emergence of what finally came to be known as the European Union. Over time, with extensive geopolitical realignment and rearrangement, we have witnessed the emergence of other similar economic cooperation blocs. We have, now, an African Union, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the South American Economic Cooperation, Mercosur, and NAFTA, for example.

In South Asia, there exists the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, which began in 1985. This is the only non-functional regional arrangement. Much work has been done at the inter-state level, though it remains largely ineffective. This is largely due to a number of conflicts, especially amongst the three larger countries: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, which used to be one country under British rule. First and foremost, the partitions and the wounds of these bloody partitions have fractured regional cooperation. Territorial disputes, rooted in the arbitrary colonial borders, are another major conflict.

Furthermore, all of these countries are more or less organized around religion and religious orientation. Almost all of these countries, even if they exhibit one prominent religion, are comprised of many minority religions. One ethnic or religious majority is likely to be a minority in a different, neighboring country. This causes conflicts among and within countries. Such conflicts spill over the borders, since the borders are quite fluid and unsettled. This is one reason why democratic institutions have not developed regionally the way they should have under normal circumstances.

Religious, sectarian, and ethnic conflicts have bolstered the creation of over-centralized states. Given the multiethnic and multinational characters of these countries, a democratic, federal system would allow communities control over resources and autonomy within specific regions. However, identity-based conflict does not permit this. Thus, centralized states tend to be militarized, since when democracy fails, states must use coercion to control populations. This coercion extends to almost every sphere of life, thus facilitating further ethnic, religious, and class conflicts. The state focuses too much on what is known as ‘integrity’, which generally means territorial integrity. In tandem with focusing on territorial integrity, these states must be ideologically-driven, because every such state, unless democracy is the dominant ideology, has to invent some overarching narrative, identity, and ideology that invariably becomes religious, ethnic, or racial. Some sort of superiority is given to a certain religion, ethnic group, or race. This, again, interacts to further strengthen centralization and militarization.

Regionally, there are occasional, actual confrontations. In Sri Lanka, there are many conflicts around ethnic, and religious, issues. The ideology of the Sri Lankan state becomes Sinhalese and Buddhist; the state seeks to impose this identity on its population. While the Tamil population is a minority in Sri Lankan, there exists a large Tamil population in India; many Tamils migrated from India to Sri Lanka under colonialism. The Tamils in India believe it is their responsibility to speak up for the Tamils living in Sri Lanka. It doesn’t really matter whether the Tamils in India have any rights or not, but they use their identity to assert solidarity with Sri Lankan Tamils. This is the same for many different identities. There are Bangladeshis in India, and Bangladeshis in Bangladesh; and people tend to assert a variety of their multiple identities, given the nature of problems with their neighbours at any given time. Thus, the Bengali Muslims asserted their Muslim identity when they felt disadvantaged in the united India, but later on, when confronted with non-Bengali Muslims in Pakistan, they chose to reassert their Bengali identity. However, they still did not want to unite with other Bengalis, who were non-Muslim. Now they refer to the Bengali identity as Bangladeshi; it has become a territorial identity more than an ethnic one.

These sorts of complications demand that nations find some peaceful, democratic solutions. Since people live on both sides of borders, they should have the possibility of freely travelling between the borders; there are divided families in every country, they should be able to reunite with their families. Economically speaking, the separate economies have developed in such a way that they are complimentary to each other, however economic regional solidarity remains lacking. For example, Bangladesh has a huge garment industry, but it does not produce any cotton. The country has to import cotton either from India or from Pakistan, these are the two countries in the region that produce cotton, or from central Asia. Bangladesh, and every country, should be able to use the region’s land routes, for rational trade and commerce; they should be importing and exporting regionally more than from distant countries. However, because of these conflicts, they can’t even freely use (for neither people, nor goods and trade) these routes. All countries are linked through rail and road links, but they cannot make use of these. Routes are blocked because of security reasons. If economic development is going to occur, the region needs to rationalize all this, and this rationalization can only happen if countries decide not to fight against each other forever.

Endless conflict like this is not sustainable, politically, economically, or socially. We had an overall population of undivided India at maybe 400 million in 1947, now we have more than 1.5 billion people. This is likely to double in the next 50 years. These economies will not be able to sustain this many people if they are divided. It is truly unimaginable as to what could happen if the situation does not change. The benefits of discarding war as an option and minimizing militarization are obvious. Reducing the military expenditure by a mere 10% a year would allow for functional social security systems regionally. Every year, we have more illiterate people, not fewer. We could be able to deal with that with this reduction in the defense budget. There is a lot of potential within the region’s countries to really expand their economies tremendously, if they prioritize regional cooperation.

I could keep listing one thousand and one reasons why these countries should stop being silly and complete this process of regionalization. Once they come to that kind of arrangement, these territorial disputes won’t hold any meaning. Wherever we witness split-community conflicts, for example, the Kashmiri population that is split by borders, the two states involved are very clear that neither of them will let the populations become independent. Thus, if these groups have to be part of one or the other country, they should live with autonomy. Once countries are peaceful, they can become more democratic. Regional solidarity is the logic of today’s world.

What is the current situation of rural labour in Pakistan?

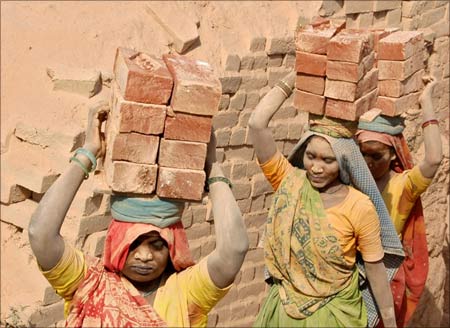

Labour rights, especially rights of rural labourers, are directly linked to ownership and control systems, which are in turn linked to the nature of the state. The British brought about the current, and very problematic, land-holding situation in South Asia after conquering and colonizing India. Before colonization, there was no private ownership of land. With the hereditary, big land-holding system in place now, it is virtually impossible to secure fundamental rights in the rural economy. When the situation worsens, which it has and continues to do, rural labour assumes forms like bonded and child labour. These issues are the consequences of abject poverty, and the fact that education is not seen as a right for children of the poor, because the nature of the economy is such that it doesn’t need an educated workforce. Since this arrangement does not have moral justification, it can only be maintained through coercion, and thus the state keeps people in a system of subjugation; mentally as well as physically.

Pakistan has a law now which prohibits bonded labour, but it is not followed or applied. Despite its ratification of the International Labour Organization’s conventions, the government turns a blind eye, and actually enforces the systems in place. Most of the bonded labourers who are bonded are iron bonded, which generally signifies debt bondage. People take loans they are not able to pay back, and their loans and interest are transferred from one generation to another. These debt bonded labourers come from lower castes and minority religions. These social factors come together to create an environment where certain sections of the population are disempowered, and in a very vulnerable position. They are forced into this kind of existence, where they feel that it is maybe in their interest to remain in this relationship. Of course, this is in no way voluntary. It is enforced.

As long as we do not restructure the system of land ownership, bonded labour will continue. Similarly, as long as we do not recognize certain basic rights for all citizens, child labour will prevail. We cannot hope to eliminate all this without establishing systems that provide alternatives. The first step towards establishing an alternative is the creation of a social security system.

How does a state establish a social security system? Right now, our first is to reduce spending in two, interrelated, areas. Firstly, we need to bring about structural changes in our economy. We currently have to borrow money from the international financial institutions, and then repay these loans. Debt servicing in all our countries is the largest hurt. Reducing debt servicing would free up funds for social security. The second issue ot tackle is our military expenses, which is linked to the issue of debt. Pakistan uses its loans to buy arms, and thus debt and arms expenditure grow in tandem. The solution is very simple: cut down on both. This alone is enough to bring about structural change. The state should stop wasting money on arms. The state should democratize. When you have a democratic government, state expenditure can decrease. These changes will only happen when people are conscious of these issues and decide to act, mobilize, and organize, not just within Pakistan, but across borders.

Log in

Log in