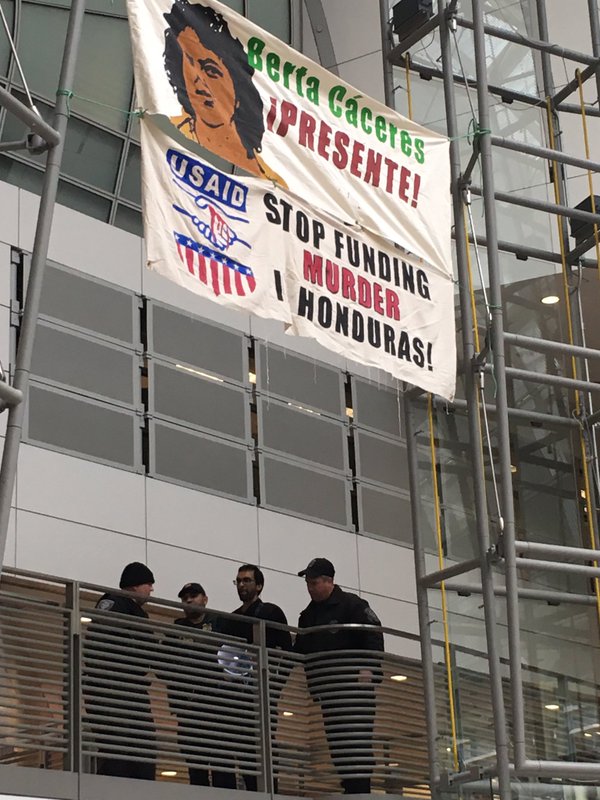

Tourists, government employees, and people strolling through downtown Washington D.C. last week likely noticed two large banners outside the buildings at 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest. One featured a drawing of Berta Caceres and the other spelled out “USAID stop funding murder in Honduras” with large block letters.

Two local activists, Jake Dacks and Nico Udugama, unfurled the banners on 14 March in front of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)’s offices. In a press release, Dacks and Udugama stated “we stand in solidarity with our dear comrade Berta [Caceres] and the Lenca people and all Hondurans who are valiantly resisting displacement in their territory.”

Just before midnight on 2 March, Berta Caceres was assassinated in her home in La Ezperanza, in Northwest Honduras. Caceres, an environmental justice and indigenous land rights activist, co-founded the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations (COPINH) in the 1990s and has become a global symbol of resistance to ecological destruction and transnational capitalism. In the 1990s, Caceres and COPINH began a series of direct action mobilizations, including road blockades and other modes of peaceful resistance, against the various hydropower projects on the Gualcarque River.

In a COPINH report, Caceres wrote:

“at the present time several international organizations are pressuring us to build megaprojects on indigenous lands — refineries, tourist resorts, and hydroelectric dams — that threaten to displace our people. But we ask: who are the people that make these proposals? We are the people who live in those areas, and we should have a right to decide what kind of projects are built on our lands.”

In 2000, Caceres described some of COPINH’s successes: “we have expelled 36 big lumber companies from our area and most of them were foreign, even from the United States.” COPINH was also successful in pressuring the Honduran government to ratify the International Labor Organization’s International Convention on Indigenous People (No. 169).

In the same report, however, Caceres described how the World Bank-funded El Tigre dam in Honduras would “displace 60,000 indigenous families, [and exact] a heavy social cost.” Despite COPINH’s traction, transnational capitalist interests continued to displace and dominate local indigenous communities.

Throughout the 2000s, Caceres and COPINH continued to mobilize against numerous large-scale, internationally-funded projects, including the Agua Zarca dam, which would effectively cut off water access for the indigenous Lenca communities in the area. That the Lenca communities who live in the area were not consulted about the dam violates international law, yet the companies funding the Agua Zarca continued with the project anyways. Even after Caceres’s murder, Dessarrollos Energeticos, SA (DESA) is still pursuing the Agua Zarca dam, with international funding through the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, and with contracting from Voith-Hydro (Siemens).

In 2008, President Manuel Zelaya, under pressure from COPINH and groups of small farmers, introduced a land reform decree to review land title claims. Zelaya’s reform aimed to restore land to the farmer cooperatives and the campesinos who had been violently coerced into selling collectively owned land to large landowners under the 1992 Law on Modernization of Land. Despite these gains, Caceres knew that COPINH’s resistance to projects like the El Tigre and Agua Zarca dams would continue to be an uphill battle.

In June 2009, the Honduran military and elites staged an illegal coup to overthrow Zelaya and reverse his plans for land reform. In the following years, Honduras became the most dangerous country for environmental activists in the world. Global Witness reports that more than 109 people were killed between 2010 and 2015 for protesting destructive dam, mining, logging, and agriculture projects. Berta’s murder is not an isolated event.

Human Rights Watch reported that at least 8 journalists and 10 members of the National Popular Resistance Front (FNRP), an opposition group that opposed the 2009 coup and demanded the reinstatement of Zelaya, were killed shortly after President Porfirio Lobo Sosa assumed power in 2010.

The post-coup government, led by President Lobo, pursued an aggressive international development and foreign investment strategy, courting transnational private investors and multinational corporations to build hydroelectric dams, mining operations, and other ecologically destructive projects.

However, Caceres and COPINH faced not only the new (unconstitutional) Honduran government, but American foreign policy interests. Even before the coup, Caceres and COPINH had called for indigenous communities in Latin America to “wake up” to the “subtle ways” that international organizations “exert great pressures on [indigenous communities] to accept their projects.”

The U.S. State Department floundered in response to Zelaya’s unconstitutional ousting. Immediately following the coup, the U.S. Embassy in Honduras sent a cable to the State Department declaring, “there is no doubt” that the coup “constituted an illegal and unconstitutional coup.” Despite this cable, the U.S. claimed that the State Department needed lawyers to determine whether the coup was indeed a ‘military coup’ and to further investigate the events, producing confusion about the events in the media, which seeped into political debates and public opinion.

Why would the State Department pretend not to know what had happened in Honduras? Because although the U.S. nominally denounced the coup, the State Department supported its political ends: the reversal of land reform policies in Honduras, the propping up of America-friendly leaders, and the continuation of socially, ecologically, and culturally destructive policies and projects for financial interest.

According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in the 12 months prior to the coup, the U.S. responded to other coups by cutting U.S. aid within days. USAID did not cut aid to Honduras after the coup, and turned a blind eye to the country’s worsening human rights conditions. In fact, USAID continues to support the Agua Zarca dam project.

The U.S. has a history of fomenting coups and instigating political upheaval in the region to maintain American influence (or, as the State Department words it, to ‘promote democracy’). Bolivian President Evo Morales has alleged U.S. involvement in coup attempts in Venezuela and Ecuador. With regard to Honduras, Morales declared, “the empire of the United States won.” Morales’s use of the word ‘empire’ is deliberate: American foreign policy in Latin and South America combined the distribution of aid to countries with horrific human rights records constitutes nothing other than imperialism poorly disguised as international development.

Just hours before the murder of Nelson Garcia, an activist who worked with COPINH and Caceres, a group of over 700 leading Latin American scholars and policy experts co-signed an open letter calling on Secretary of State John Kerry to suspend foreign aid to Honduras until the government changes its human rights record.

Jake Dacks and Nico Udugama’s allegation that USAID funds murder in Honduras is not a far-fetched conspiracy theory. Indeed, providing aid to a government that fails to prevent (or is perhaps entirely responsible for) the murder of activists and opposition leaders is the American status quo. And the status quo is not only irresponsible, it is simply unacceptable.

Sources:

https://web.archive.org/web/20000816200746/http:/www.epica.org/advoc.htm

http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/03/22/gustavo-castro-soto-and-the-rigged-investigation-into-berta-caceres-assassination/

https://www.greenleft.org.au/node/61365

http://www.justforeignpolicy.org/node/774

Log in

Log in