The problem posed by the current refugee crisis in Turkey, Greece, and much of Europe is, on one hand, an economic and political morass and, on the other hand, a very simple human crisis. There should not be much debate in terms of helping refugees. Despite this, the governments of many European nations have turned a man-made calamity into a bargaining chip, one that exacts a larger human cost by the day. Examining the political motivation for the EU’s inaction does little to alleviate human concerns, but does help explain the intricacies of bureaucratic failure.

First, some context. As more and more refugees stream arrive in Europe, the European Union has struck a potential deal with non-member Turkey for help. As detailed by The Guardian’s Jennifer Rankin, EU representatives and ex-Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu agreed to a 1 to 1 ratio for refugee settlement (one European migrant for every one refugee returned to Turkey).

Bare statistics reveal some harrowing realities: of the already 3 million refugees in Turkey, nearly 363,000 have made it to mainland Europe and an additional 2,000 arrive on the Greek shores each day. EU chief Donald Tusk openly hoped that “the days of irregular migration to Europe are over,” where the agreement aims to halt the horrors of human trafficking and arrange movement on a more sanctioned level. The problem, then, with such politicized change is the ignorance to the needs of refugees.

Survival, for migrants, often demands illegality – they are fleeing turmoil and potential death. Turkey, the nation where refugees will be deported, holds nearly as much danger as Syria, simply because of proximity. Sergio Peçanha, writing for theNew York Times, uses Aleppo as an example. The city’s border is now closed, trapping migrants on each side of potentially disastrous regional divide. The Aleppo decision further enforces Turkey’s institutional failure, one that Peçanha breaks into four categories: unemployment, poor housing, limited education access, and bureaucracy. The Turkish state, in efforts to curry European favor, fails refugees at nearly possible juncture, offering little to no support.

Rigorously detailed by Peçanha and Patrick Kingsley of The Guardian, among others, refugees stand little chance of improving their lot in Turkey. The government offers temporary status which affords refugees’ rights to health care and education but no international refugee status or a clear path to citizenship. Bank accounts are necessary for resident permits and, both tragically and ironically, resident permits are a requirement for bank accounts. Only about 10% of all refugees in Turkey will be eligible to work. Only one in three Syrian children attend school in Turkey, partially because of the need for illegal child labor to offer some financial respite to migrant families. What was originally a deal to normalize migration quickly devolves into an abusive free-for-all where the nation with the lowest interest in protecting human rights accepts migrants in a clear ploy to grab a larger piece of the EU pie.

The Turkish government does not have the purest of intentions. According to both Kingsley and Rankin, the Turkish government and EU have entered into a double bind where the migrant deal is contingent on the relaxation of visa restrictions into Europe for some 75 million Turkish citizens. Such lessened restrictions would arrive at a moment of increased authoritarian intolerance towards political dissent within the Turkish media.

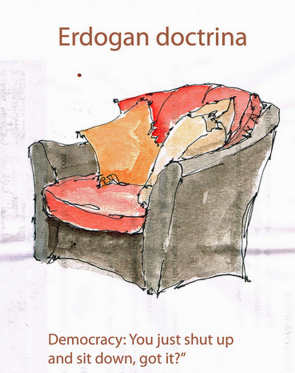

Rankin’s article briefly mentions President Erdoğan’s recent seizure of the news agencies Zaman and Cihan as a gesture towards increasingly restricted free speech in Turkey. Kingley’s tells an equally questionable tale of censorship, where Erdoğan charged a Turkish journalist, Can Dündar, under a rarely used archaic piece of German law that prohibits slighting foreign leaders when Dündar published a critique in a German magazine. The story in question, accusing the Turkish government of selling weapons to Syrian rebels, held obvious negative political impact for Erdoğan and his regime. What appears more frightening is the lack of European criticism. Because of the need for migrant aid, even the furthest left of EU members (despite those governments and contingents shrink due to right-wing paranoia) has remained eerily quiet. Turkey’s role in the Syrian refugee crisis will apparently continue unabated and, apparently, unwatched.

Damien Gayle of The Guardian aptly follows the double-illegality of the EU’s planned migrant removal. UN officials, most certainly experts on international law and the status of refugee rights, decried the deal as a twofold betrayal: collective deportations without any opportunity to claim asylum offer the first breach of the law, and the good-faith guarantee of observed rights by the Turkish government offers the second failure. Even worse, Gayle outlines some of the obvious and distasteful justifications for such an arrangement. Members of British Parliament, as per Gayle’s reporting, have already begun the alarmist table-pounding of insurgents sneaking into Europe with the countless thousands of refugees. While terrorism poses a real threat to Western Europe, refugee movement offers only one of a near-infinite bevy of options for illegal immigration. To harp on the weakest of citizens, at their most prone moment, seems to heap insult onto injury.

All of the political justifications work backwards. Instead of targeting the area of need – helping millions of displaced people find a suitable and conflict-free migration zone – most European nations place a newfound xenophobia at the foreground of tacit economic fears, especially at a time of EU instability. Even still, the predictability of such a Western failure does nothing to empower refugees. There are two worlds viewing the Syrian crisis, one upper and one lower, producing diametrically opposite evaluations of the situation. Consider two quotations, one from EU Chief Donald Tusk, and another from a Syrian migrant. Sounding impossibly out-of-touch, Tusk praises Turkey as “the best example for the whole world for how we should treat refugees… Nobody should lecture Turkey on what to do.” In direct contrast, and stressing the immediacy of their situation, an unnamed refugee outlines their reality: “We will repeat our trip again and again if needs be, because we are running away in order to save our lives.”

There is a falsified tension in the political and real perspectives of a crisis. Political answers aim to uphold a certain tenet of civil society in answering a terrifying question. Realistic answers disregard propriety and nuance because it no longer exists, often exploded in civil war or natural disaster. What such a deal like the EU-Turkey bargain defiantly restates is a return to the established order. Political considerations will trump realistic ones. The sun still rises, the tides still goes in and out and, again apparently, there will always be turmoil and for the most vulnerable of the human community.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/23/angela-merkel-turkey-visit-refugee-camp-gaziantep

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/23/merkel-accused-turning-blind-eye-syrian-refugees-turkey

Written on April 30th, 2016.

Log in

Log in