To the contemporary left, the Paris Commune is an iconic event. However, like the Latin prayers I used to mumble as a Catholic altar boy, the Commune may still be revered but the intensity and relevance of what it meant at the time and still means today may escape us. Many things have happened since 1871: the Russian Revolution, the rise and fall of fascism, the Chinese Revolution, anti-colonial struggles, feminism, and the environmental movement. The Paris Commune can easily get lost as just one more event in the long narrative of struggle for a better world. In fact, it is important to remember that the Paris Commune, in the short time of its existence, was a political and social earthquake that terrified the ruling classes and inspired working people all over the world. It also gave us two of the most quintessential songs of the left as Eugène Pottier wrote l’Internationale while in hiding after the massacre of the Communards and Irish socialist Jim Connell wrote the anthem “The Red Flag” as a tribute to the communards.

The Paris Commune had many links with the long struggle for Irish freedom from British domination. In the late 19th century, Ireland was a major political issue for the left as Karl Marx, a supporter of Irish independence, wrote that it was the key to undoing the British Empire – at that time, the most powerful entity in the world. It is natural then that there were historic connections between the Paris Commune and Ireland’s struggle.

Following the failed 1848 rebellion of the Young Ireland movement, several Irish revolutionaries fled to Paris. Among them was James Stephens who became one of the founders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) better known as the Fenians. Stephens learned from French revolutionaries of the time and adapted their ideas in organizing the underground IRB, which at its height had tens of thousands of members. He even approached General Gustave-Paul Cluseret to be commander-in-chief of the Fenian forces for the planned rising in Ireland. Cluseret refused but did take part in the Fenian attack on Chester Castle in 1867. The general then went on to become the leader of the defense of the Paris Commune in 1871.

In the decades following the bloody repression of the Commune, it was dangerous for anyone to celebrate or honour its memory openly. The communards became a bogeyman used by reactionaries to frighten people and stifle progressive voices. In Ireland, the Catholic Church also played a role in demonizing the memory of the Commune. Ireland did not possess the anticlerical attitudes that existed in France and were evident in the Commune. Indeed, the Catholic Church was seen as an essential part of Irish culture and thus an element in the resistance to British imperial rule. Thus, for decades any mention of the Commune or socialist politics was anathema in Ireland When some Irish members of the first International once tried to meet in a small office, the gathering was interrupted when the landlord burst in calling…

…those present a set of ruffians and blackguards. He said he had been led to the room on the pretense that the meeting was to be for a discussion of the labour and wages question, and that he would sooner burn the house over his head than hire it for the nefarious purposes of Internationalism.

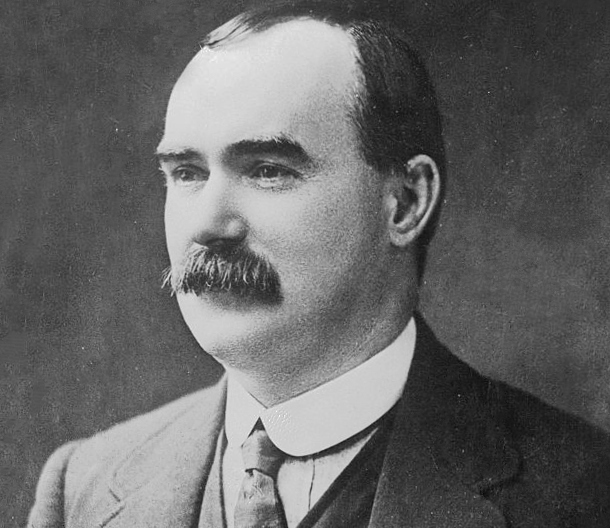

The relevance and memory of the Commune returned openly with the arrival on the scene of James Connolly (1868 – 1916) in 1896. Connolly was a revolutionary theorist, a trade union organizer, a prolific writer, an Irish Republican, a feminist, and a committed anti-imperialist. As a young radical in his native Edinburgh, Connolly met and was influenced by Leo Meillet, a French refugee who had been a leading communard in Paris. In Dublin, Connolly founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party, which organized open commemorations of the Paris Commune. Writing in the Workers’ Republic in 1899, Connolly said,

“The Commune, if it had been successful, would have inaugurated the reign of real freedom the world over – it would have meant the emancipation of the working class;”

While seeing the Commune as an inspiration to build a better world, Connolly also drew the lesson as to how vicious reaction to social progress would be. In his seminal work Labour, Nationality and Religion, Connolly referred to the repression of the Commune as a clear example as to how the ruling-class will respond to revolutionary activity:

It is a well-established fact that from the earliest revolutionary outbreak known down to the Commune of Paris, or Red Sunday in Russia, the first blood has been shed, the first blow struck, by the possessing conservative classes. And we are not so childish as to imagine that the capitalist class of the future will shrink from the shedding of the blood of the workers in order to retain their ill-gotten gains.

Connolly’s interest in the Commune was not only based on political theory, however. In the early 20th century, Europe was clearly drifting towards a war between the imperial powers. The socialist parties were calling on workers to refuse to fight for the ruling class and, in Lenin’s words, ‘turn the imperialist war into a civil (i.e., class) war’. Meanwhile, in Ireland, Ulster Unionists, the descendants of English and Scottish Protestant colonists given land taken from native Irish in the 17th century, were vowing violent resistance to the implementation of Home Rule in Ireland. Home Rule would have given a modicum of self-government to Ireland, but even this limited step to self-determination was an abomination to the Unionists. The Home Rule bill had passed in the British House of Commons, but the Unionists organized an armed militia, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), to oppose its implementation. The UVF had open support from the British military, which turned a blind eye as thousands of rifles were smuggled into Ulster. The British Conservative Party leader Bonar Law openly expressed support for reactionary violence and civil war when he said: “I can imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster can go in which I should not be prepared to support them.” On both the European and Irish scenes, Connolly saw the likelihood of imminent violence and potentially revolutionary situations with the consequent need to prepare a radical response.

Connolly studied the street fighting and use of barricades that occurred during the Commune and wrote articles and gave lectures on the lessons to be learned. Even more importantly, he founded the Irish Citizens Army (ICA) during the great Dublin lockout in 1913. Originally established to protect workers from police attacks, the ICA became a politicized workers’ militia, the first “red” army in Europe. Connolly’s commitment to gender equality was notable as women were treated equally in the ranks of the ICA. For example, Constance Markievicz held the rank of captain in the Irish Citizen Army and commanded the St. Stephen’s Green garrison during the 1916 Rising.

Connolly was greatly disappointed by the failure of European socialists, with a few honourable exceptions such as Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht, to oppose the war. He watched in horror as hundreds of thousands of workers joined to ranks of the armies of their countries only to be slaughtered for the benefit of the ruling classes. He was determined to act in this situation and joined with the radical nationalists of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Irish Volunteers to plan an insurrection in 1916. However, he never abandoned his class consciousness and his awareness that the working class has its own goals that should not be subordinated to the interests of other classes. As the Irish Citizen Army marched out on Easter Monday, Connolly told them “In the event of victory, hold on to your rifles, as those with whom we are fighting may stop before our goal is reached. We are out for economic as well as political liberty”. For Connolly, the Rising was a blow for national liberation but was also an internationalist action in line with the Stuttgart resolution passed by the Socialist International, directing its supporters to use war crises to mobilize the masses to overthrow capitalism.

The 1916 insurrection, commonly known as the Easter Rising, lasted a week and was brutally crushed by the British Army. Though empty, Liberty Hall, the home of the Irish General and Transport Union and the Irish Citizen Army, was shelled from a warship on the river Liffey and completely gutted. Connolly was commander-in-chief of rebel the Irish Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers now known under the collective name of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). While bad luck, poor communication, and conflicting orders limited the Rising largely to Dublin rather than being a nation-wide event, the rebels fought well, using the tactics Connolly had learned from his study of the defense of the Paris Commune. The British forces suffered 142 casualties while the IRA losses numbered 66 killed in action.

After the rebels surrendered, Connolly, who had been wounded in the fighting, was court martialed and shot by a firing squad. He was still so gravely wounded that the British had to tie him on a chair to shoot him. The British military command and leading capitalists were anxious that he be executed before the British government began issuing pardons.

The Easter Rising was a pivotal event in modern Irish history as the majority of Irish people soon supported the rebels and their goal of freedom from the British Empire. In 1918, the national liberation party Sinn Fein won 73 out of 105 Irish seats in the British parliament with the mandate to refuse to go to Westminster and instead to establish an Irish republic with a parliament in Dublin.

Unfortunately, Connolly’s death was a fatal blow to the left wing of the national liberation movement. As a result, the working class and its demands were marginalized in the new Irish Free State. The Rising was quickly romanticized into a myth of blood sacrifice and Christian imagery, and its radical elements were erased or forgotten. The social content of the Rising has often been overlooked and downplayed and has only recently begun to come back to light. The 1916 Proclamation read from the steps of the General Post Office in Dublin was a radical document for its time and clearly shows the influence of Connolly. It called for secularism, gender equality, civil rights, and the ownership of Ireland by the people of Ireland. This led the British establishment of the time to fabricate and howl about a so-called Sinn Fein/Bolshevik alliance, following the Russian Revolution in 1917. Parallels to the Paris Commune were also prevalent in immediate denunciations of the Rising. The Irish Catholic said that “to find anything like a parallel for what occurred it is necessary to have recourse to the bloodstained annals of the Paris Commune.” The Daily Sketch wrote that “the wild scenes of the past week recall the savage horrors of the Commune.”

Connolly would no doubt have been amused by these hysterical parallels for he saw in the Rising the same positive message that came from the Paris Commune. Working people can organize, act, and take control over their own lives and society.

In The Civil War in France, Marx wrote that “The greatest measure of the Commune was its own existence, working, acting under circumstances of unheard difficulty.” In the same way, the existence of the 1916 Irish Republic, though crushed after a week, affirmed the right of the Irish people to self-determination, and the world would not be the same after.

This inspiration of the Commune, brought to Ireland through the work and life of James Connolly, motivated Irish workers through the decades of recent armed conflict in the North of Ireland. Today, a renewed and revitalized left-wing Sinn Fein party sits in the Northern Ireland Assembly and is the official opposition in the Irish parliament. Its objective is to unite the country in the next decade and create a new Ireland of equals in which the content of the 1916 Proclamation becomes a reality. In 2019, a James Connolly Visitor Centre/ Áras Uí Chonghaile was opened on the Falls Road in Belfast with the mission of ensuring that a new generation of Irish citizens and those who visit from across the world are introduced to James Connolly and his ideas. Áras Uí Chonghaile is thus honouring Connolly’s legacy and carrying on his internationalist message that goes back to the Paris Commune. Of course, the most fitting tribute to the life and work of Connolly will be the creation of a united, socialist Ireland.

References:

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/04/james-connolly-paris-commune-easter-rising-tactics

https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1899/05/home.htm

https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/index.htm

https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/seeking-the-real-irish-revolution/

Log in

Log in