Rushdia Mehreen (RM): Tell us about Fatimah, the kind of life she is living and the struggles she faces. And why this story was important to you.

Veena Gokhale (VG): The novel gradually reveals that Fatimah is a farmer and belongs to an ethnic group called the Aanke. The Aanke village, Ferun, where Fatimah used to live, was on fertile farmland, along the banks of the river Feruni. The Aanke led a peaceful life and used traditional farming techniques, though they innovated as well. They sold their crops in a nearby town. The land was communally held, and it was claimed by settlement; hence they have no land deeds for it.

The government forces them to move, because they want the land for an agriculture project, and promises them compensation. But a year later, very few families have received the money.

Leaving the land is a shattering experience for Fatimah and her community. Along with the her father, husband and children, she moves to another Aanke settlement, in another part of the country, where they are helped by her brother-in-law. Her mother goes to the North West Highlands with a large part of the community, to try and settle on new land there. Many young men go into towns to do hard labour and send money back to their families. Fatimah’s father dies soon after the move because he is so tied to the land that leaving it breaks his heart.

Here is an excerpt from the book: “On the eve of their departure from Ferun, a slow burning anger claimed Fatimah. All this time, there had only been anguish over the multiple losses — land, home, family — lost, broken, scattered. That night she made a resolution that she would find a way to bring them all together again.”

When I lived in India, and I was a journalist there in the 1980s, stories of dispossession of rural people to make way for so-called development projects were common. Activists started asking the questions: what was appropriate development? Who was benefitting from the kind of development that was taking place, and who was losing out? I was deeply affected by what was happening; it was horrifying to witness such large-scale relocations. Some families had to relocate multiple times. And the dubious benefits went only to the elite. Landgrab and exploitation of the poor is a universal phenomenon with historical roots.

Later on, the character of Fatimah, dispossessed, but strong and resilient, appeared in my imagination, and I felt that I must tell her story. This is my second book. The first was short stories largely set in Bombay.

RM: Which brings me to the protagonist, Anjali. Do you identify with her at all? We do see many broad stroke similarities in terms of professional identity, origin and so on. Tell us if the character reflects your personal experiences.

VG: Anjali is an Indo-Canadian who works for HELP: Health, Education and Livelihood skills Partnership, a Canadian international development organization with its main office in Toronto and project offices in different parts of the world, including Karmoga. It’s at HELP’s field office that Anjali meets Fatimah.

I can’t say I identity more with Anjali than I do with Fatimah, or with her housemaid Mary, another key character in the story. But yes, my own expat experience of living and working in Dar-es Salaam for two years, via CUSO, did inform Anjali’s story. There is the challenge of learning a local language, a kind of isolation because you have left a familiar workplace and home, as well as friends behind. I found the office set-up in Tanzania much more top-down than in India or Canada. In the novel, Anjali clashes with the Chairperson of her Board, Grace, who undermines her and her work. Also, I drew from what I observed of expat life and the expat enclaves people live in, which are really a bubble, rather cut off from local realities.

RM: Land for Fatimah talks about the dispossession and displacement of Fatimah, her family and their whole community from their ancestral land. These themes are omnipresent in contemporary struggles and a lot of us are involved in solidarity, if not directly affected by these grave injustices. To what extent were you making references to struggles such as that of Indigenous peoples across the world, but also closer to home, here in so-called Canada, and to the struggles of dispossession and displacement of Palestinian people? In short, what were your inspirations for taking on this topic, besides your stay in Africa?

VG: I very much wanted to tell a universal story about the dispossession of a small farmer, as well as a story of an expat international development worker, and the unusual friendship that develops between them. Both go on a quest to find new land for this dispossessed community, and encounter many obstacles. At the same time, I wanted to give a lot of detail that would make the story vivid. I deliberately set the novel in an imaginary country, which I sketch as a former British colony in east-Africa. That way I could play around more freely with all the elements and make my points, albeit through the device of storytelling. In terms of the big themes I wanted to talk about power structures, corporate greed, governmental corruption.

Here is an excerpt from the later part of the book that may perhaps partly answer your question: “So much land and yet all this land hunger, a bottomless need that had always been there. India, Canada, Kamorga - everywhere the same thirst for land and the same practice of getting hold of it through any means possible, hoarding it, wrenching it away, denying it to needy people.

In Bombay they had reclaimed land back from the sea, dredged it from salt marshes, but there still hadn’t been enough. Millions slept under the sky every night, still others under plastic stretched over poles. But even those cardboard and tin huts were razed to the ground, poles wrenched from under the plastic awning, lives callously tossed asunder.

In North America there had been the greatest land grab in history. An entire continent, inhabited, seen as "empty land" and taken over: unfair treaties signed with the natives, treaties signed and ignored, no treaties signed at all, the original inhabitants of the land put on reserves, their children shoved into residential schools and barred from speaking their mother tongue and practicing their ways; abused. The horror! The absolute, incredible, palpable horror of it, the fallout everywhere — native men begging on the street, lying drunk, native children sniffing glue, native women turning to prostitution and drugs, "disappearing," native men filling North American jails.

In Africa, the colonial powers had come and gone, but their legacy shone bright. People without a roof over their head or a way to earn a living. People without basic services — water, toilets, public transport, electricity — to speak nothing of healthcare or education. People driven away from their traditional lands, working as labourers on someone’s export-oriented farm, or in a mine whose wealth ended up abroad.”

RM: Indeed. And there’s forced displacement of the poor (e.g., the Narmada Valley project in India) and the refugees resulting from ongoing imperialist projects. The displacement by dispossession is an omnipresent theme, particularly in the global South. The prologue of your book describes a slum demolition in Bombay (Mumbai). Could you talk about these examples, and the connections in terms of power structures, corporate greed, governmental corruption and so on?

VG: I was actually very disturbed by the Narmada Valley/Sardar Sarovar dam projects in India. In fact, I wrote about it as a journalist and greatly admired the Narmada Bachao Andolan, which was a grassroots movement protesting the dam. For those who may not know, this is one of India’s most massive and controversial projects in terms of human and environmental impacts. Fatimah, like millions of people around the world, is an IDP, or internally displaced person.

In the book I try to make a link between an unjust development model and the rural poor coming to cities and ending up in slums, which can then get razed. One figure I heard for the number of slum dwellers worldwide was as high as 1 in 8 people.

In the Bombay of the 1980s, slums were routinely bulldozed. The slum that gets erased in the Prologue is where Anjali, then a schoolgirl living in Bombay, taught reading and writing to a group of women, as a volunteer teacher. That horrific experience, seeing the homes of people she knew destroyed, is one of her motivations later on for committing to finding land for Fatimah.

I don’t want to give the suspense and plot of the book away, by giving out too many particulars! But here is another excerpt: “Anjali had come face-to-face with that naked greed and power and disregard for human life for the first time…

She was used to dealing with abstractions — feudalism, patriarchy, big government; globalization, neoliberal policies, corporate control. She had studied what the oppressive weight of these forces had done, were still doing, to people, and to their world. She had read innumerable reports and sat through countless conferences where well-dressed professionals had explained how these forces had twisted the lives and broken the hopes of the poor, of people at the margins, as they were called. She had met some of the "victims," transformed into "stakeholders" by development projects.

But it was the very first time that these forces had assumed human form — become a figure that threatened her directly, palpably. She had not entirely crumbled under that gaze, but it had shaken her. She had come to realize how puny she was, how limited her resources, particularly here in a country not her own.”

RM: The book sheds light on the situation in Africa, its colonisation, the kind of life people are living, and the role played by the international development NGOs and the different conceptions of social change. The service model of NGOs (provision of schools, drinking water and such) is challenged as being a band-aid solution, and there’s a celebratory note around the possibility of a red revolution. What are some of your closing thoughts on the situation in Kamorga? Is there a ray of hope against the backdrop of dispossession and displacement?

VG: Fiction is a great way to show the complexities and contradictions of life and explore emotions and motivations. You can also show different points of view through dialogue, for example. Anjali is a liberal, essentially, and believes in the work and methods of NGOs, and certainly her own NGO. But in Kamorga her belief is shaken for a number of reasons.

Here she meets Hassan, a Marxist-academic who works as a consultant for HELP. They are both drawn to each other, even as they argue. Hassan believes that all the working poor in the country need to be organized and fundamentally change the system. One part of the country has a mining industry, and there is, offstage, a character called Mahamud Siyahi, the youthful, fearless leader of the Mine Workers Front, a fantastic orator and a savvy negotiator and organiser. This man gives Hassan hope that change will come.

I present another point of view through Anjali’s colleague, Anne. Anjali questions the efficacy of the work of international development organizations, while Anne defends it. Here is what Anne partly says: “I find that I am far away now from those academic discussions about aid. I see the need here and I want to respond. I think we’re learning all the time and trying to apply what we learn. We’re helping advocates, feeding them information, even though we don’t advocate directly ourselves. So in that sense we’re involved in policy change. Perhaps the most important thing is that we bring new ideas; I’d go so far as to say new inspiration.”

Fatimah’s story also ends on a hopeful note. While there is one great defeat, there is also a possibility opening up. I believe that life is never all bleak, and progressive change is worth striving for. My book is about serious issues, but it’s not depressing!

As for the future, I would love to go back to Kamorga in another novel and check out the red revolution that perhaps may have come about through Mahamud Siyahi’s leadership!

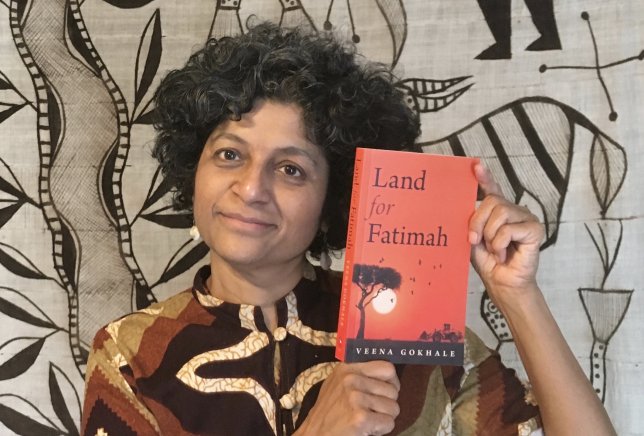

Note: The book can be bought from Guernica Editions and Amazon.

To know more about the author: https://www.veenago.com/writing/index.html

Log in

Log in