Most tactics aimed at decreasing income inequality involve a combination of more progressive taxation schemes and increased availability of social services. By this logic, alleviating inequality hinges upon effective tax reform (increasing income tax for the rich, raising corporate tax, ending tax havens) in tandem with the provision of more accessible and generous social services. There is nothing inherently flawed with this formula: ensuring that the wealthy contribute their share and that the government safeguards the rights to housing, education, health, food, and overall wellbeing ought to redistribute wealth and reduce inequality.

The problem lies not in the policies themselves, but in the scope of their approach. Instead of assuaging inequality’s symptoms, we ought to focus on prevention in the form of a long-term and transformative cure. Redistribution schemes, while necessary, are not sufficient. A more primary and fundamental approach tackles income inequality before taxation.

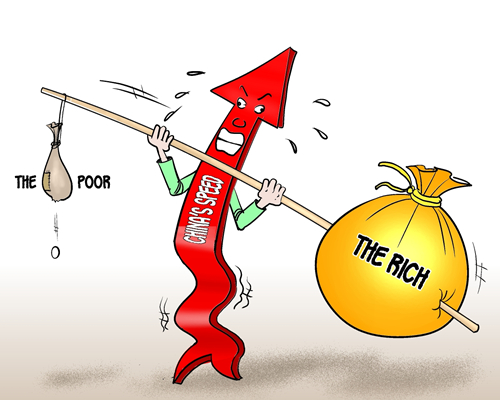

The statistics detailing income inequality are well known. It suffices to note that in the past decade in the United States, the salaries of corporate CEOs have skyrocketed to as high as 400 times that of the average production worker. The minimum wage has not substantially increased, not even in proportion to the increased cost of living. This relationship reflects a global trend to the tune of an old adage: the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.

Efforts to raise the minimum wage face bureaucratic hurdles and conservative opposition while the highest incomes swell due to governments’ failures to implement democratic, effective income regulation. Instead of remedying this ever-widening gap, we would do well to address its underlying causes.

A major factor in the exacerbation of income inequality in the past several decades was the fragmentation of unified, effective, and supported labour movements in the late 20th century. A study published by the Centre for Labour and Social Studies found that, as trade union membership declined in 16 OECD countries between 1966 and 1994, income inequality increased substantially. From 1980 onwards, the income share of the richest 1 per cent in Canada, the United States, and United Kingdom climbed to unprecedented levels, coinciding with a sharp decrease in union membership.

This should come to no surprise: if workers are not unionizing to collectively bargain for higher wages, better working conditions, and stricter health and safety regulations, then corporations are not actively held responsible for providing higher wages, better working conditions, and stricter health and safety regulations. Capitalism’s invisible hand does not ensure shared economic prosperity. It serves corporate greed.

The increased income inequality from the late 1970s onwards reflects the increasingly anti-labour international political climate, crystallized in Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal regimes. In 1981, when some 13,000 workers of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) threatened to strike, Reagan issued an executive order disbanding the union, effectively firing almost 11,000 workers.

The PATCO strike is often cited as the decisive event in the dissolution of the American labour movement, the realignment of class power, and the exasperation of income inequality. In his book Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, The Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America, Joseph McCartin declares that “no strike since the advent of the New Deal damaged the U.S. labour movement more.”

The PATCO strike is not an isolated incident, though it is a historical pivot point. At the beginning of the century, the top 10 per cent of Americans claimed nearly 40 per cent of the national income, while union membership was as low as 10 per cent. This gap continued to widen through the 1920s: the top 10 per cent continued to earn as much as half of the national income. In 1935, the National Labor Relations Act, part of the New Deal, encouraged unionization and established workers’ rights to collective bargaining. As a result, union membership soared throughout the 1930s, corresponding with a dramatic decrease in income inequality. Throughout the ‘Great Compression’ into the 1970s, economic prosperity was largely shared: the portion of the national income taken by the rich was slashed by one third.

However, beginning in the early 1970s with the economic recession, political culture shifted, and unions came under attack. Union-busting techniques became status quo. Politicians, courts, and public policy cracked down on labour, culminating with the PATCO strike of 1981. Since the 1980s, union membership has steadily declined, income inequality has risen to the levels witnessed in the 1920s, and corporate accountability has hit an all time low.

The correlation between increased income inequality and decreased union membership cannot be attributed to market forces, union mismanagement, a lack of faith in the collective bargaining process, or confounding factors. Income inequality is the direct result of conservative ideology and political will. Anti-labour policies in the later half of the 20th century have underwritten a political culture blind to the source of its own disease.

Reversing the trend will require more than redistributing the wealth grabbed by the rich. Progressive taxation is a step in the right direction, but generating equality necessitates the stimulation and support of a powerful and effective labour movement. Government can no longer afford to back the rich and squash labour; international financial institutions can no longer prescribe anti-labour policies alongside their ball-and-chain loans. Achieving shared economic prosperity and environmental sustainability relies on reform, political action, democratic constraints on top incomes, and social influence. It’s due time we start biting the (invisible) hand; it has failed to feed us.

http://classonline.org.uk/docs/2013_04_Thinkpiece_-_labour_movement_and_a_more_equal_society.pdf

Log in

Log in