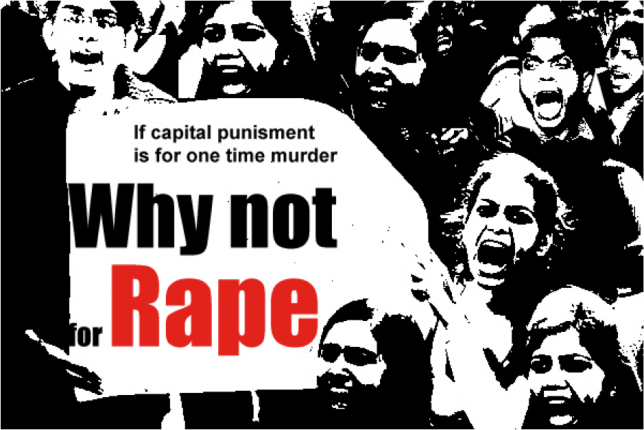

Nation-wide protests have provoked a re-consideration of existing rape laws in India. These were triggered by the fatal rape incident in New Delhi this past December, in which a 23 year old student was gang-raped in a public bus. Under the Indian Penal Code, a convicted rapist can suffer a prison sentence of 7 to 10 years. Sparked by the anti-rape protests, however, this sentence has been reviewed and amended by the Indian Parliament on March 21st to extend the minimum sentence to 20 years. Further changes have been made to include the criminalization of voyeurism and stalking, as well as the death penalty for convicted serial rapists.

While the heinous gang rape in December brought India’s endemic of sexual assault to the spotlight, a surge of additionally reported sexual assault incidents against girls and women in the following months have intensified the push for stricter punishment. Among these reported incidents include the highly publicized cases involving two female tourists, one Swiss and the other British.

In March 2013, the Swiss victim and her husband were camping in a remote part of central India when a dozen or so men gang-raped the woman and beat and robbed them. That same month, a British woman staying at a hotel in Agra was compelled to jump out of her second floor window, after being harassed by the owner to open her door.

Two more cases were reported only weeks later, this time involving two five-year old girls, one of whom succumbed to her injuries and died May 27th, while the other is in stable condition but must undergo reconstructive surgery. Both girls were lured by men familiar to them and were violated within walking distance of their homes. These reports demonstrate the near ubiquity of sexual violence across India where, be it in the busy streets of a cosmopolitan city or the communal space of a farmland, every female body is a walking potential victim. This especially rings true seeing as the staggering statistic of reported assaults only goes to underscore the likely higher number of unreported cases.

Aside from their relative brutality and recency since the December incident, the above cases received considerable media attention due to the victims’ demographics, namely, in their being foreigners and very young children. These factors stress that the presence of sexual violence has become an urgent epidemic that no member of the female sex is immune to including those who are supposedly the most protected - children and tourists.

While long-awaited government attempts have finally been implemented to toughen the century-old penal code for rape, these efforts seem to merely scratch at the surface of a human rights issue that continues to plague women and children across the nation. With the statistics of reported rape cases increasing incrementally by the year, one wonders at the rampant incidence of unreported rapes in a society where the topic of sexual assault remains relatively taboo, making rape not only a human rights issue, but a social one as well.

Following the nation-wide protests of the past few months that have garnered international attention, Rashida Manjoo, an independent UN expert on violence against women, travelled to India to investigate and report on sexual assault laws. Her conclusions were founded on a number of disappointing observations: “My mandate has consistently voiced the view that the failure in response and prevention measures stems from a Government’s inability to and/or unwillingness to acknowledge and address the core structural causes of violence against women”. Manjoo’s report sheds light on the deep-seated stigma that not only discourages victims from reporting incidents of assault, but encourages perpetrators to commit the crimes in the first place, as they are enabled by a socially-sanctioned attitude that places just as much blame, if not more, on victims than their rapists.

Several women’s rights organizations that are at the forefront of the protests stress the pivotal role that society’s patriarchal belief-system plays in fueling the endemic of sexual violence. As Ruchira Gupta, the founder of ApneAp a women’s rights group observes, India’s “women are in danger even before they’re born”. This inherent danger is founded in gender-divided attitudes, whereby women live in the fear of being victimized while men shift the blame of sexual assault on the victim. Results from a survey conducted by UN Women reveal that up to 95% of women in New Delhi feel unsafe in public, while three-quarters of the surveyed men agree with the statement that “women provoke men by the way they dress”. More disturbingly, 51% of these men have confessed to having committed an act of sexual assault in a public space.

In condoning sexual violence, these pervasive views perpetuate a patriarchal cycle in which women have been, and continue yet, to be treated as second-class citizens. In a society in which sex-selective abortions, female infanticides and dowries continue to prevail in spite of being illegal, rape becomes an additional factor to add to the supposed burden of the female sex. As these misogynistic crimes are founded on the view that women are financial liabilities to their families, being a victim of rape usually implies bearing a mark of shame and dishonor that only adds to their statuses as liabilities. This stigma primarily accounts for the prevalence of unreported incidents.

Ultimately, the stigma of rape surrounds the archaic, primitive belief that once violated, a woman’s value to her family, community and society is greatly diminished – she becomes, in essence, unmarriageable. This myth, however, is countered by the recovery of many victims of sexual assault as they learn to deal with the trauma of sexual violence. While the 23 year-old student in New Delhi eventually succumbed to her wounds and passed away, she lives on in the legacy of a new-age women’s rights activism that has burgeoned following her rape. The recently amended rape laws in India will probably have a bare minimum effect in curbing the prevalence of rape, but perhaps its most promising aspect lies in its opening up of nationwide discourse on an otherwise taboo topic.

Log in

Log in