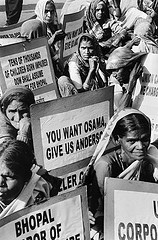

More than 25 years after Bhopal was turned into a city of death on the morning of December 3, 1984, the provincial High Court delivered its judgment on June 7, 2010 convicting former Union Carbide India Chairman Keshub Mahindra and seven others to a maximum of two years in jail. Warren Anderson, now 89 years old and Chairman of the Union Carbide Corporation USA at the time of the disaster in 1984 did not feature in the judgment. He had visited Bhopal soon after the accident and was taken into custody but released after diplomatic intervention, possibly involving the then President of the US Ronald Reagan and the just installed Prime Minister of India, Rajiv Gandhi. Since then Bhopal activists have been demanding the extradition of Anderson and death by hanging. The light sentence of Indian officials of the Union Carbide and no verdict on Anderson naturally created a fury on the part of the Bhopal disaster survivors, activists, sympathizers of the Bhopal victims and Indian journalists; to paraphrase, “TWO YEARS FOR 20,000 DEATHS!”

Capitalist democracy is a highly developed institution; most of the devices used to deal with various circumstances, including disasters and accidents, have been accepted as legitimate both by the right— for whom they were designed— and by the left whom they fooled. It is based on punitive measures meted out to high officials. In India, the Railway Minister usually resigns after a severe train accident; the Food Minister resigns after famines. These punitive measures spare the system and bypass the main issue. It was therefore to be expected that a demand for the extradition and hanging of Anderson, and life imprisonment of Indian officials of the Union Carbide, and a posthumous verdict against Arjun Singh, the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh at the time of the disaster, and Rajiv Gandhi, the then Prime Minister, would have satisfied the activists and spared them the tedious task of organizing protests and signature campaigns.

On the other hand the Bhopal disaster and everything that followed, including the High Court Verdict, also raises another question or, rather, a set of questions. I have been peripherally involved in the Bhopal issue right from the beginning but my efforts have been directed towards accumulating evidence in support of adverse health effects of the disaster especially on survivors and pregnant women and their fetuses on one hand, and analyzing the possible causes of the disaster on the other hand. All my studies have been published. I even incurred the wrath of Indian activists when I wrote that the deaths in Bhopal could possibly not have happened by hydrogen cyanide because what leaked from the storage tanks was not cyanide and even if all of it got converted into cyanide, it could never the reach minimum concentration of 300 parts per million (ppm) necessary for its lethal effects. In contrast methyl isocyanate (MIC) which actually leaked, can kill at less than 10 parts per million. Cyanide leaves no residual effect if it does not kill but we all know that MIC does— and did. But none of this is the most significant part of the Bhopal disaster. Nor is the leniency of the High Court judgment. Neither two years of imprisonment can be matched with 20,000 deaths, nor can 20 years or life imprisonment, or hanging of all surviving officials including Anderson. Punitive measures have not checked recklessness in the past and would not do so now.

The Bhopal Disaster poses three basic questions. One, should India entertain hazardous industries like the one that was in Bhopal at all? If the answer is yes, then what should be done to minimize the chances of disaster? The disaster having taken place, as it did in Bhopal, what should be done to minimize the suffering of the survivors and the families of the dead?

In my opinion, no country can afford to desist from developing industry, including hazardous industries, to progress and meet the future needs of its population. The former Soviet Union did it. The present China does it. And of course hazardous industries exist in all developed capitalist countries. Approximately 1.4 million tons of hydrogen cyanide are produced annually, of which the USA accounts for 50 percent. Even methyl isocyanate-based plants exist in the USA, Germany and Japan. When the late Chief Minister Arjun Singh, one of the champions for communal harmony in India, lobbied to get Union Carbide to set up its operations in Bhopal he thought he was bringing industry to backward Madhya Pradesh and was being instrumental in producing a pesticide much needed for agricultural production. Indeed such measures did make India food-sufficient— food availability and its equitable distribution is a different issue. I do not think that the Union Carbide plant was of much inferior quality than the one in West Virginia. There were no settlements adjacent to the plant when it was built, though it was much too close to the railway station and the two major hospitals in Bhopal. What was missing in the Union Carbide operation in Bhopal was that it made no provision for the specific condition of India, its work culture, and the commitment of its officials towards safety in the operation of an industry as hazardous as it was. Why should water leak into pipes carrying MIC? I might add that once water reached the MIC tank, what followed could not have been prevented even if all safety features were in operation. In my opinion India, or a foreign establishment in India, should make provisions for establishing a proper safety and operational work culture at all levels and this is true for all hazardous industries, including nuclear power plants and mining industries.

Perhaps the lenient High Court judgment should have aroused stiffer demands for compensation rather than for stiffer penalties. British Petroleum is being forced to commit more than twenty billion dollars to clean up the mess it has created in the Mexican Gulf. Why should India be lenient towards Dow Chemicals, the current owners of Union Carbide?

Union Carbide ceased operations in Bhopal after the disaster but it left hazardous chemicals which have become a part of the ground water. It is going to eventually cause a greater hazard than the gas disaster but at a slower and less noticeable rate.

If the anger against the High Court judgment focused on these issues, one could feel that Bhopal Disaster has taught a useful lesson. Blood for blood is another matter!

Log in

Log in